Mensahi Ginen i Gehilo' #15: Decolonization Miasma

One thing that I struggled with when I first became more conscious about issues affecting Guam, especially around political status, was the question of why more people weren't interested in this and why so few people were committed to the idea of changing it. For my entire life, for the entire lives of my mother and father, for the entire lifetimes of my grandparents, Guam has been a colony of the United States. The face of American colonialism in Guam has changed significantly. My grandparents grew up at a time when Guam was strictly segregated and Chamorros were openly treated as inferior to white Americans. Today, although people on Guam do regularly experience second-class treatment at the hands of the United States at multiple levels, it is easy to dismiss this as simple ignorance or lack of respect and not tie to it a larger political relationship.

Para Guahu, ti ya-hu na mañåsaga ham yan i familia-ku gi un colony. Ti ya-hu na esta para kana' kuatro na siento na såkkan manmafa'ga'ga'ga' ham taiguini. Este na impottante na finaisen para Hita komo taotao, "hafa na klasen taotao hit?" Kao dikike' pat satbåhi na taotao hit? Pat kao un åmko' yan gaitiningo' yan taotao? Anggen ti mangga'ga' hit yan annok na manaotao hit, sa' håfa ta aksesepta este na fina'ga'ga'? Sa' håfa ti ta keketulaika este?

This is what led me to discuss this issue in my academic research. For my thesis in Micronesian Studies at UOG, I interview more than a hundred Chamorros, the majority of whom were born prior to World War II and had a very different cosmology than me. It struck me in ways I could not shake, how they could be proud of Chamorros and their culture in one sentence, and then in the next act as if Chamorros were mangeyao yan manaisetbe. In more than one interview, an elder stated emphatically that Chamorros as a people, especially before are manmetgot yan manmesngon, especially because of the way they would live prior to the war, closely connected to the land and the sea for their sustenance. But when I would push this issue in terms of decolonization and argue that we should work to rekindle that spirit and teach it to our youth and restructure our society today around those ideals, suddenly that strength would vanish. When thinking about before, whether before the war or before colonization, Chamorros were proud and strong, but today they are weak and dependent and rather than talking about sustaining themselves and taking care of themselves, they should just depend on the US to take care of them, since that is the way of the world.

This gap, which you could label in a number of ways theoretically, persists up until today. When you consider this however, the apathy or fear of decolonization makes much more sense. Even if it is frustrating, at least you can understand it better and seek ways to counter it and help people see a decolonized future as something not fearful, but exciting and something that we should come together and work towards.

Here's an article from The Pacific Daily News from last year, which discusses the overall miasma on the island towards the issue. I like the article however, because it features several critical voices on the topic of decolonization, and if you are interested in learning why it does matter, debi di un ekungok este siha na bos.

*********************

Copyright © 2015 Guam Pacific Daily News. All Rights Reserved

Para Guahu, ti ya-hu na mañåsaga ham yan i familia-ku gi un colony. Ti ya-hu na esta para kana' kuatro na siento na såkkan manmafa'ga'ga'ga' ham taiguini. Este na impottante na finaisen para Hita komo taotao, "hafa na klasen taotao hit?" Kao dikike' pat satbåhi na taotao hit? Pat kao un åmko' yan gaitiningo' yan taotao? Anggen ti mangga'ga' hit yan annok na manaotao hit, sa' håfa ta aksesepta este na fina'ga'ga'? Sa' håfa ti ta keketulaika este?

This is what led me to discuss this issue in my academic research. For my thesis in Micronesian Studies at UOG, I interview more than a hundred Chamorros, the majority of whom were born prior to World War II and had a very different cosmology than me. It struck me in ways I could not shake, how they could be proud of Chamorros and their culture in one sentence, and then in the next act as if Chamorros were mangeyao yan manaisetbe. In more than one interview, an elder stated emphatically that Chamorros as a people, especially before are manmetgot yan manmesngon, especially because of the way they would live prior to the war, closely connected to the land and the sea for their sustenance. But when I would push this issue in terms of decolonization and argue that we should work to rekindle that spirit and teach it to our youth and restructure our society today around those ideals, suddenly that strength would vanish. When thinking about before, whether before the war or before colonization, Chamorros were proud and strong, but today they are weak and dependent and rather than talking about sustaining themselves and taking care of themselves, they should just depend on the US to take care of them, since that is the way of the world.

This gap, which you could label in a number of ways theoretically, persists up until today. When you consider this however, the apathy or fear of decolonization makes much more sense. Even if it is frustrating, at least you can understand it better and seek ways to counter it and help people see a decolonized future as something not fearful, but exciting and something that we should come together and work towards.

Here's an article from The Pacific Daily News from last year, which discusses the overall miasma on the island towards the issue. I like the article however, because it features several critical voices on the topic of decolonization, and if you are interested in learning why it does matter, debi di un ekungok este siha na bos.

*********************

Guam Residents Lack Enthusiasm for Decolonization

by Jerrick Sablan

Pacific Daily News

November 27, 2015

by Jerrick Sablan

Pacific Daily News

November 27, 2015

Members of several indigenous rights groups in Guam acknowledge

many residents aren’t interested in joining their fight for

self-determination.

This lack of passion about choosing Guam’s

future relationship with the U.S. is a reversal from previous decades,

when many on island were more aggressive in pushing for Chamorro rights,

according to one activist.

The process of determining Guam’s political status has stalled over the years.

Trini Torres, of the group Taotaomona Native

Rights, said many of the activists who spoke out in previous decades

are getting older, and she’s encouraging younger Chamorros to take up

the fight.

Torres is pushing for the island’s independence — one of the options for Guam’s future political status.

"I want my freedom," she said. "I want to be free. I don’t want to feel like a slave."

The island’s Independence Task Force of the

Commission on Decolonization met Wednesday to discuss its plans for

educational debates at the island’s high schools.

The task force’s mission is to educate

residents about Guam’s political status options. The island could take

three routes — statehood, free association or independence.

Guam currently is an unincorporated territory of the United States.

A political status plebiscite for native

inhabitants was originally scheduled to take place in 1998, but has been

postponed several times, primarily because of a lack of resources

committed to the effort and a failure to register and educate eligible

voters about the three options.

Guam’s plebiscite would be a non-binding

vote, intended to measure the preferred political status of Guam among

native inhabitants.

Local law limits participation in the

plebiscite to people who fit the legal definition of "Chamorro" — those

who became American citizens by the Organic Act of Guam in 1950. The

vast majority of these residents also are ethnically Chamorro.

The plebiscite now is scheduled to take

place after an education campaign is completed, and after the Guam

Election Commission has determined enough eligible native inhabitants

are registered to participate in the vote. However, the commission’s

executive director and Gov. Eddie Calvo have said the law related to the

date of the plebiscite might need to be

clarified.

Importance of deciding

Victoria Leon Guerrero, from Our Islands are

Sacred, said there aren’t many people who have the time to get involved

in activism, but it’s important more people be aware of the island’s

political status and the need to change it.

Leon Guerrero is part of the independence task force.

The island’s political status as an

unincorporated territory doesn’t afford it a seat at the table for major

decisions, including the military buildup, Leon Guerrero said.

She said it’s important the U.S. lets Guam decide the relationship it wants before proceeding with the buildup.

The buildup only increases the island’s dependency on its colonizer, she said.

The energy being put into the buildup should instead be focused on what political status Guam should have, she added.

It will take both the local government and the community to push for the political status change, Leon Guerrero said.

One way to do it is to make it like a

political campaign, getting people who support the various political

statuses to go out and get support for their cause, she said, adding, if

there can be a show of force with thousands of people speaking on the

issue and making a community driven effort, it could move it forward.

The capacity of local indigenous groups is

limited today because it’s difficult to juggle daily life and activism,

she said, but the groups can help get people informed and feel invested

in the cause.

Fight for independence

Cathy McCollum, magahåga of Chamoru Nation,

said the U.S. still holds Chamorro land and water, and it’s important

for the people to have those resources back.

"Give us our sovereignty," McCollum said.

Torres, from Taotaomona Native Rights, said

for people who don’t believe Guam can be independent, look at smaller

island nations, such as Palau, who are doing well.

She pointed out that America fought for its independence from the British and asked why can’t Chamorros do the same.

"It’s not important for us to be free?" she asked.

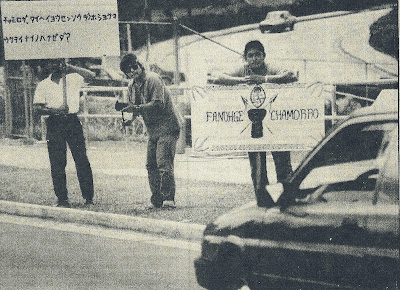

Activists today, she said, aren’t as aggressive as those in the past, including the late Sen. Angel Santos.

Santos was known for his involvement in protests concerning various Chamorro rights issues during the 1980s and 1990s.

Through the years

Robert Underwood, president of the University of Guam, has seen the issue of decolonization evolve over the decades.

In the 1960s, the issue of political status

was brought up when the Legislature wanted to study the issue in Guam

because of the other Trust territories. Guam at the time had several

options and voted to keep the status quo with improvements, Underwood

said.

In the 1970s, the focus turned to drafting a

constitution. Back then, Underwood and others opposed making a

constitution because Guam’s political status had to be decided before a

constitution could be written.

Then the next thing was focusing on self-determination and who’s considered part of the "self."

It was decided that "self" meant the Chamorro people since they were the ones that were colonized, he said.

He said he was part of indigenous rights

groups in the 1980s, and now sees that political issues like

decolonization aren’t pushed as they were before. But it’s because

Chamorros today are focusing more on a cultural renaissance, he said.

He encourages Chamorros to learn more about the issue and become more informed.‘Too complicated’

The Calvo administration has made decolonization a priority and has stated it would try to have a plebiscite by 2017.

Underwood said the vote is being complicated by too many rules.

He suggests a vote be conducted and have people come in and state they are Chamorro and give them a ballot.

Most people who aren’t Chamorro would respect the process and wouldn’t portray themselves as Chamorro, he said.

Hawaii did something similar in an election

and they didn’t see many people coming in who weren’t Native Hawaiians,

Underwood said.

Making the voting process easier would make the vote happen a lot sooner, he said.

"I personally think it’s too complicated," he said.

He also noted the vote wouldn’t have any effect on Guam’s status because it would basically be a formal opinion poll.

The results would only be a suggestion on what the Chamorro people who were colonized want to move forward, he said.

"It was the Chamorros who were colonized, so it is the Chamorros who need to decolonize," he said.

Copyright © 2015 Guam Pacific Daily News. All Rights Reserved

Comments